The Sword, chapter II: The Rapier 2500 - 1500 B.C:

In chapter I it was suggested that the sword and novel warrior ideologies appeared on the northern fringes of the Sumerian Uruk trading network at the end of the 4th millennium. There seems to have been a large scale rupture with a flow of people southwards: the phenomenon of rich kurgan burials disappears from Northern Caucasus, only to reappear further south in Transcaucasia. Here new kurgan traditions replaced the older Kura-Arax culture, while Kura-Arax related ceramics spread southwards into large parts of the Near East as the Uruk network crumbled from c. 3000 B.C.Alaca Hüyük and the Trialeti CultureIn the millennium after Arslantepe there are few clues to the continued use of the sword. The most important is the "Royal tombs" at Alaca Huyuk in Central Anatolia. Here at least three long swords were discovered. The longest from burial A (A'26) has a long tang, sloaping shoulders and a total length of 82,4cm. All of these swords have simple cross-sections, lenticular or flat/hexagonal – no ribs or grooves. The cultural context of these burials from c. 2500 B.C., is poorly understood. Often they are linked to kurgan burial traditions of the Caucasus.

Museum display of a tomb from Alaca Huyuk. There is also a significant clue from the Caucasus region. The Maikop culture and the wealth of their kurgan tombs disappeared around 3000 B.C., and the phenomenon reappear further south in the Transcaucasus. This first horizon of kurgan burials in Transcaucasus is named Martkopi-Bedeni, and has not yet yielded any swords. The following horizons of the Trialeti culture, have provided swords. The earliest of these seems to be Saduga in Georgia, belonging to Trialeti phase I. This is merely 49 cm long, but has now a pronounced mid-rib and a significant level of tin. The date of this phase should be somewhere between 2500-2200 B.C. The importance of the Saduga sword is that it represents the beginning of a continuous development towards the rapier. Samtavro burial 243, also from Trialeti culture, transition phase 1-2, contained a fully developed rapier: 99,3cm long, high central rib. The Samtavoro blade thus represents the earliest known developed rapier, and dates to c.2000 B.C. if not earlier. The major study of the Aegean swords has been that of N. Sandars, and her main trajectory of the evolution of the long sword is still often referred to. She concluded that the Aegean rapier seemed to appear fully developed in Mallia, Crete at the end of MM II/beginning of MM IIIB.The LevantN. Sandars believed that the process from dagger to sword occurred in the Levant, as seen in the early rapier from Byblos. The Byblos rapier was seen as the direct predecessor of the Aegean rapier, and is dated to c.1800/1850 B.C.

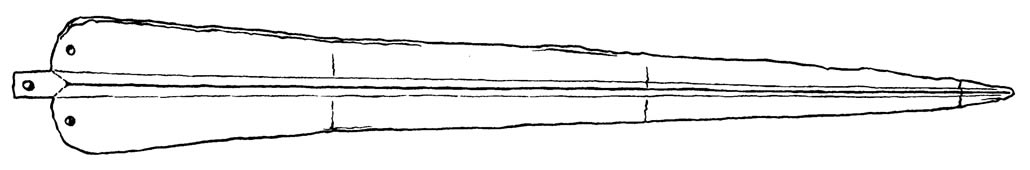

The sword from Byblos. Length: 57 cm (Sandars 1961). Recently S. Shalev has provided further clues to the development. The long sword from Beth-Dagon near Jaffa in the Levant, was for a century attributed to the Sea People, the Shardana, from the end of the Bronze Age, based on some resemblance to scenery on Egyptian wall paintings. Closer scrutiny demonstrates that the Beth-Dagon sword is an elongated version of the daggers from the Levantine Middle Bronze Age I (type A). The characteristic trait of type A daggers is a high number of rivets along a waisted hilt section. Metallurgical analysis also favours an early date: a blade from the age of the Sea Peoples would have contained a fair amount of tin. The Beth-Dagon sword contained no tin, but rather 6% arsenic (with a higher content coating). Thus, the Beth-Dagon sword is the better candidate for the earliest sword in the Levant, possibly before 2000 B.C. And, importantly, this sword demonstrates that local hilt designs were combined with foreign ideas of length.

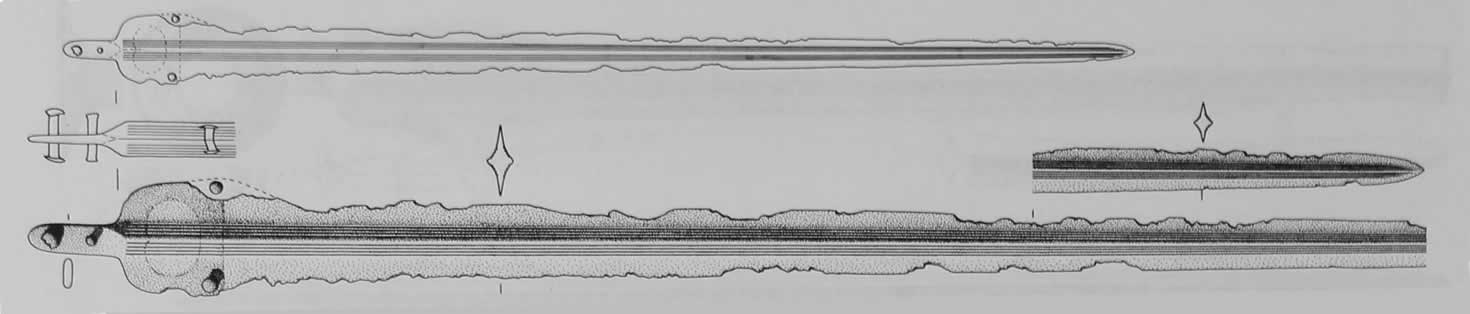

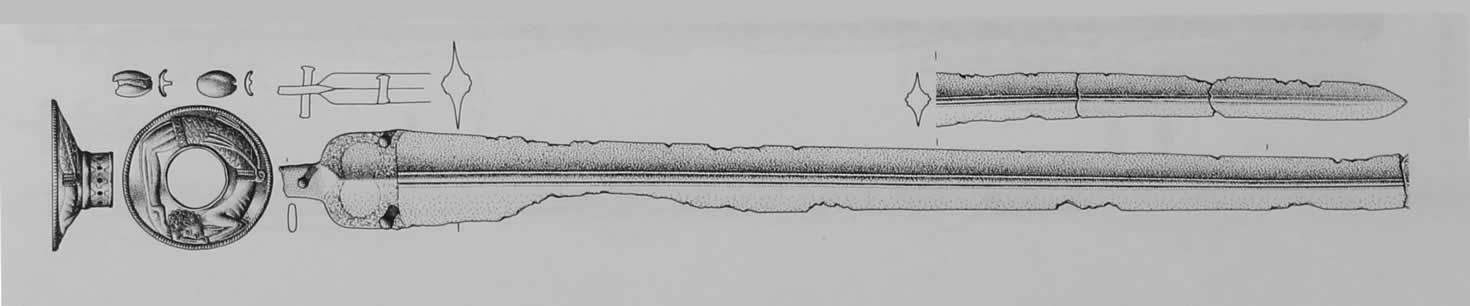

The sword from Beth-Dagon. Length: 108cm. It is still difficult to give the Levant an essential role in the development of the rapier and the sword, as the numbers are so few compared to the Transcaucasus and the Aegean. Importantly, examples of straight swords not bordering on dagger-lenghts, are rare through the rest of the Bronze Age in this area. One might even be tempted to turn the arrows of influence around, and see the Byblos sword as made in the Aegean.Crete, the Peloponnes and the rest of the AegeanConventionally, the Aegean rapier (the type A sword) is believed to have appeared first on Crete, at the end of MM II. Recent developments in absolute chronology has made the MM II and MM III phases shorter, MM II: 1875 B.C. (or 1850) - 1750 B.C. (or 1700 B.C.) and MM III: 1750 B.C. (or 1700 B.C.) to 1700 B.C. (or 1675 B.C.). This regards the swords found in the first palace at Mallia (although its first palace context has been contested in favour of a MM III context) (see Killian-Dirlmeier 1993: 26p.). The result is that the appearance of type A swords on Crete within MM II need not be much earlier in actual years than type A swords in MN III at Mycenae (grave Iota, circle B) (Dietz 1991: 261pp.).

The two type A swords from the first palace of Mallia, Crete. Length: 81,2 and 74,1 cm (rearranged from Killian-Dirlmeier 1991). Thus, the Mallia swords demonstrate that the type A rapier was fully developed before 1750 B.C., and they demonstrate from the very start two traits that would be characteristic to Aegean sword design for centuries: a) excuisite central ribs combining functionality and aestetics with fine plastic ribs and grooves, and b) complex multi-part hilts often with precious materials like gold and ivory. This continous through the Horn- and Cross series to the appearance of the Naue II with its simplified cross-section c. 1200 B.C.

Transcaucasus and the AegeanHow might we understand this swift spread of novel metal forms from the Caucasus to the Aegean? Local hilt designs clearly indicate that it is not a question of trade in weaponry. It is rather a question of a new fashion of fighting, one that originated on the northern periphery. And the least understood part of this puzzle, at least for western researchers, is the Trialeti culture of Transcaucasia. One should also note that the Old Assyrian empire that came to dominate large parts of the Near East with its immense network of organized trade – has not given any findings or imagery of long swords. A range of objects in the Trialeti burials were for decades seen as imported or influenced by Minoan/Mycenaean objects, and always seen as secondary and younger. It is now clear that for instance the cauldron from kurgan XV, Trialeti phase III, has a virtually identical parallel in Shaft Grave IV, Mycenae. Thus, the end of the Trialeti sequence runs parallel to Late Helladic I on the Aegean mainland. Bringing Trialeti into the foreground, early and with a range of innovations in metallurgy and weaponry, changes the larger picture fundamentally. It casts the origin of the Mycenaean wealth buried in the Shaft-Graves into question. The specifics of the burial tradition, the chariot equipment (horse-harness and whips), decorative styles (rope-an-pulley), the socketed spear and the rapiers, could all be linked to earlier examples to the east, from the Trialeti culture in the south to the Sintashta culture in the southern Ural foothills.What seems certain is that movement of people, through trade, raiding and migrations, along an east west axis, escalated sometime before 2000 BC. These movements probably went across the mainland through Anatolia and the Levant, as well as through Bosporus and the Black Sea. While the Near Eastern armies adapted the barbarian spoke-wheel chariot, they did not adapt the straight sword of extreme length. This became characteristic for the upper elite, the war-lords of the barbarian tribes on their northern periphery.

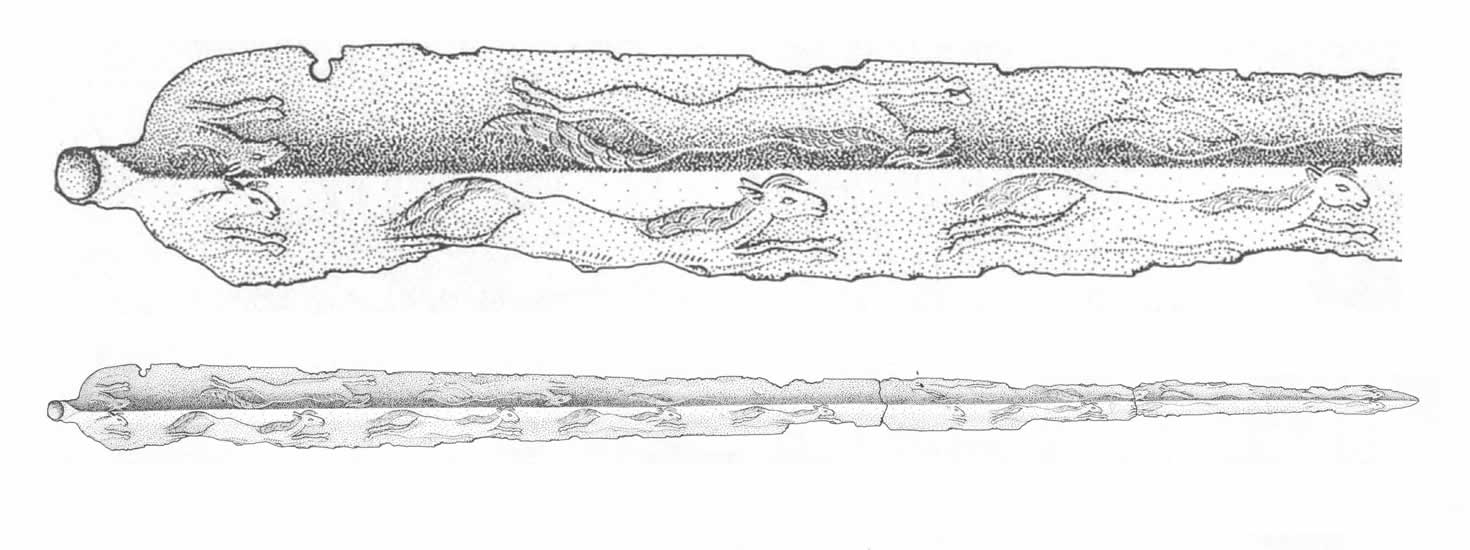

The scenery from a silver goblet from Karashamb, belonging to Trialeti phase II, might suggest that the more ordinary warriors used spear and dagger. The long rapier might thus have been used for duels and man-to-man combat between the upper elite. The Mycenaean swords probably give the clearest hint to what it was all about: the long, sharp blade with running horses in low relief speaks of ideals of fighting styles and swift manoeuvres, and probably linked up to poetry describing sword fighting heroes in battle. The "Running Horses" Rapier was found along with 90 other swords in Shaft Grave V at Mycenae!

Scenery from the Karashamb silver goblet, Trialeti culture c. 2000 B.C. (Digitally edited by this author). A story of battle, beheading of the loosers and listing of the spoils of war.

Type A sword with running horses, Mycenae Shaft-Grave V.

|

|

|---|---|

The Bronze Age Sword Series includes three items from this stage.

LILO(Lilo, Georgia, c. 2000-1900 B.C.) |

Trialeti culture. Tanged blade, pronounced central rib, bronze (10% tin). Total lenght (excl. pommel) c. 114cm (the image is a preliminary model-image, the actual sword might differ in finish and minor details). |

|

|---|---|---|

BETH-DAGON(Beth-Dagon, Jaffa, Israel, c. 2000 B.C.) |

Blade with broad tang with 12 rivets, pronounced central rib, bronze. Hilt: polished walnut and ivory pommel (imitation). Total length c. 108 cm. (the image is a preliminary model-image, the actual sword might differ in finish and details). |

|

MALLIA(Mallia, Crete, c. 1650 B.C.) |

Blade with tang and 2+2 rivets (Type A, var. 2). Total length c. 83cm (bronze only). (the image is a preliminary model-image, the actual sword might differ in finish and minor details). |

|